From Graffiti to Gallery: Sean Knipe’s Unconventional Path

Sean Knipe’s introduction to art was less a formal beginning than a moment of pure discovery. As a child, he recalls standing transfixed by paint as it spread, shifted, and settled. That early encounter with movement, chance, and transformation left a lasting impression.

What began as fascination soon became necessity. Painting evolved into more than expression; it became a way of navigating the world. A language through which Knipe learned to see, listen, and orient himself. Growing up in South Africa without access to formal art education, his creative drive found an outlet in graffiti, a decision that ultimately led to his expulsion from high school but affirmed his determination to pursue life as an artist.

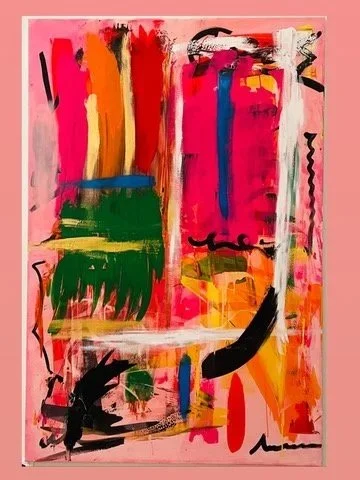

Knipe later earned a degree in Graphic Design from the Technical University of KwaZulu-Natal, taking a nontraditional route that continues to shape his practice today. Working primarily with oil paint and techniques such as clean and dirty pours, his work embraces unpredictability and process. Often described as evocative and introspective, his paintings reflect his core aim: to create art that moves the viewer emotionally, intuitively, and without over-explanation.

Sean, when do you know a work is finished, or do you ever?

I don’t think a work ever announces its completion clearly. For me, it’s more a sense of tension resolving—or at least stabilizing. When further intervention starts to feel like explanation rather than exploration, I know it’s time to stop. Sometimes that certainty only comes after stepping away and returning with fresh eyes.

Greatest inspiration or influences?

My influences are broad and not always visual. I’m inspired by music, particularly improvisational jazz and electronic soundscapes, as well as by writers who work with ambiguity and fragmentation. Visually, I’m drawn to artists who allow space, risk, and vulnerability to remain visible in the work rather than resolving everything into a polished statement.

What role does intuition play versus planning in your work?

Intuition is central. I may begin with a loose framework or intention, but I rely heavily on responding to what’s happening on the surface in real time. Planning sets the conditions, but intuition drives the decisions. The work often reveals what it needs as it develops.

Are there materials or gestures you return to because they feel essential to you?

Yes—certain marks, layers, and methods of erasure recur naturally. I’m drawn to processes that leave traces of earlier decisions, whether through scraping back, staining, or layering. These gestures feel essential because they mirror how I think about time, memory, and change.

How does working in South Africa shape your practice, even indirectly?

Working in South Africa inevitably shapes my awareness, even when the work isn’t overtly referential. There’s a constant presence of complexity—social, historical, and spatial—that informs how I think about fragmentation, layering, and contradiction. It creates a sensitivity to what is visible and what remains unresolved.

Are there rhythms, landscapes, or histories that seep into your work unconsciously?

Absolutely. I think landscapes, both physical and psychological, enter the work through rhythm rather than representation. Histories surface less as narratives and more as pressure: a sense of accumulation, disruption, and persistence that influences how forms interact and resist cohesion.

Do you think abstraction still carries political or social weight today?

Yes, though often in quieter ways. Abstraction can resist fixed meanings and easy consumption, which in itself can be a political stance. It allows for complexity, uncertainty, and multiplicity—qualities that feel increasingly important in the current social climate.

Has your relationship with your own work changed over time?

It has become less controlling. Earlier on, I was more concerned with outcomes and coherence. Now I’m more comfortable with ambiguity and with allowing the work to exist without fully resolving itself or aligning neatly with intention.

Do you see your practice as evolving—or looping back on itself?

Both. Certain concerns return again and again, but each time from a different angle. It feels less like repetition and more like circling—revisiting familiar territory with new experiences and questions shaping the approach.

Anything else you would like to share?

I’m interested in keeping the work open—open to interpretation, to failure, and to change. I see abstraction not as an escape from reality, but as another way of engaging with it.