Sara Naim: Dissolving Boundaries Through Art

London-born Syrian artist Sara Naim (b. 1987) creates work that challenges our most fundamental assumptions about separation and connection. In a world increasingly defined by rigid boundaries between nations, identities, and ideologies—Naim's multidisciplinary practice offers a radical alternative: what if the lines we draw to separate are actually points of profound connection?

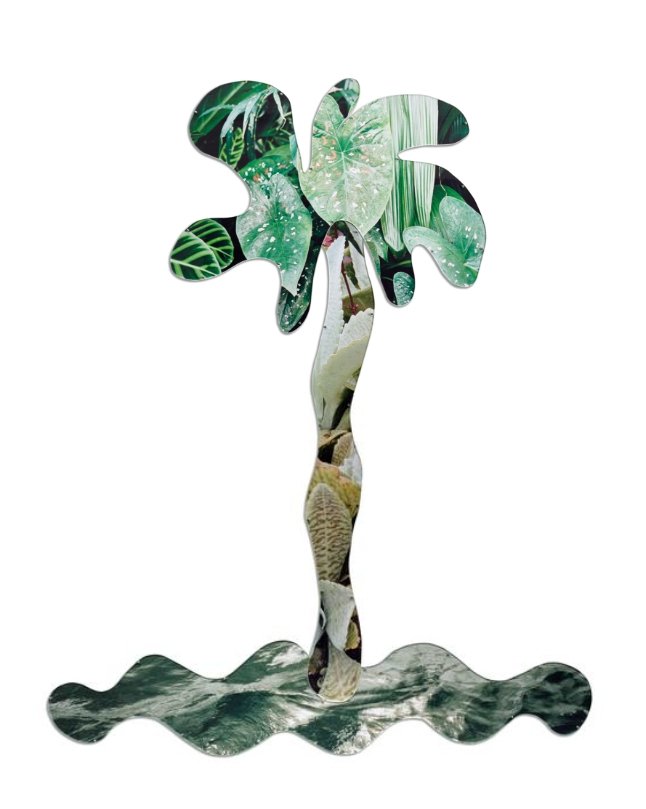

Her artistic methodology defies easy categorization, forensic precision with performative gesture and philosophical depth, Naim crafts photographs that function as sculptures, sculptures that reveal themselves as paintings, and paintings that reference the documentary quality of photography. This deliberate blurring of media mirrors her conceptual preoccupation: exploring how perception itself is shaped by proximity, boundary, and polarity.

Trained at London's prestigious Slade School of Fine Art (MFA, 2014) and London College of Communication, her work has been exhibited internationally, including solo exhibitions at The Third Line in Dubai, Parafin in London, and Hayward Gallery Concrete, establishing her as a vital voice examining how rigid notions of separateness operate across individual, social, and national frameworks. In the following interview, Naim discusses the evolution of her practice, the tension between representation and reality, and why the boundaries we construct may be the very things that bind us together.

Q: Your work often explores how boundaries connect rather than divide, how has your own experience of being Syrian and living between London and Dubai shaped that perspective?

I think national boundaries are a more obvious divide that we constantly cross, but on a deeper level, we are constantly playing with thresholds—whether it’s blushing when we’re shy or a racing heart when we’re nervous. Our emotions constantly externalize themselves. So I’m not sure that my personal transitoriness influences my perspectives on boundaries. My initial influence was actually Taoism, and learning about how opposites don’t need to operate in duality. That informed my perspective on borders, exploring the connection between both sides of the line.

Q: You draw parallels between plant migration and human migration. What inspired this connection, and what do you think it reveals about belonging and displacement?

I worked with Syrian refugees in Athens, where there’s a strong familiarity between the land and vegetation there and the Levant — the arid Mediterranean climate, where dry soil holds tall pine trees and jasmine vines. There’s a parallel between the movement of people and the movement of plants, except plants aren’t bound by borders. They transgress in a way that humans were once able to. Similarly, whenever my family drove from Damascus to Beirut, we passed identical terrain. It’s only in modern history that we’ve chopped land up, claimed it, excluded and included, and territorialized the earth. We should learn from native plant species propagating freely across borders.

Q: In your statement, you mention “romanticized attachment to place.” How do you personally negotiate nostalgia for Syria with a broader, more fluid sense of identity?

Nostalgia and romanticization set us up for failure—it warps memory and creates attachment. I don’t see Damascus for what it actually is; it’s become a new place that I’ve constructed through its romanticization. I think we constantly do that—project meaning and associations onto objects and places that either elevate or diminish them. We rarely see things as they truly are.

Q: You often use scientific tools and visual languages — microscopes, photographic processes, and cellular imagery. What draws you to these methods, and how do they shape the way you explore perception?

Sight is a continual process that governs how we perceive the world. I recently heard a talk by scientist Sara Walker, who described sight as one of the most groundbreaking inventions and explained how it complexifies over time. Initially, nothing on the planet could see — for a long time, life existed without sight. Photoreceptors were eventually invented, and as multicellular organisms evolved, some of these cells developed into eyes. Humans then advanced these multicellular eyes by creating technological “eyes” such as telescopes and microscopes, which allow us to observe the universe at both larger and smaller scales. Sight constantly shapes the way we perceive ourselves and the reality we inhabit. So, I use scientific apparatus as a medium, and that plays into my interest in both the physiological and existential aspects of sight.

Q: What are your greatest inspirations or influences?

I look at a lot of art and have been really admiring Salman Toor’s paintings. But my strongest influence is being a mother of two young boys. Motherhood has made me trim the fat - both in my practice and in life - and it’s helped my work become more honest.

Q: What type of music do you listen to when you are working on your art?

A lot of podcasts- Duncan Trussell, Philosophize This!, Alan Watts, BBC world service, Martyr Made, Lex Friedman.

Courtesy of the artist